Ten Greatest Films

Limiting your film taste to ten movies is impossible. The decadal Sight and Sound poll has been famously requiring directors and critics to do so since 1952, but everyone knows that ten films do not and cannot represent a person’s entire film taste. Neither do these ten films represent mine entirely, but perhaps they do a better job than any other set of ten films.

I say this upfront because my notable omissions were arguably much more plentiful and as a result meaningful than these ten films alone. I say this as a reminder that there are many more films that I hold in the same regard as these ten. (Here a short list: The Birth of a Nation (1915), The Last Laugh (1924), Seven Chances (1925), Masquerade in Vienna (1934), Angel (1937), Bicycle Thieves (1948), Seven Samurai (1954), The 400 Blows (1959), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Modern Romance (1981), Eyes Wide Shut (1999)...) But without further ado, here are what I consider the ten greatest films in chronological order: (Note: potential spoilers)

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

Produced and released in the same year as the first sound picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), Sunrise is perhaps the single greatest achievement of silent cinema, summarising with breathtaking emotional power the various cinematic techniques that have been developed in the decades up until then, but also inventing a good many on the way. The film is possibly most notable for its unique four-part structure, as it not only switches its thematic focus during each act but also the very genre that defines the tone of the film. As a result, Sunrise does not confine itself to any rules and transcends the medium in such astounding ways that it seems nearly impossible not to swoon at the pure poetry Murnau creates here. As if that isn’t enough, the film also delivers one of the most beautiful and creative musical scores to ever accompany a film. If I had to pick just one movie for this list, it would be this one.

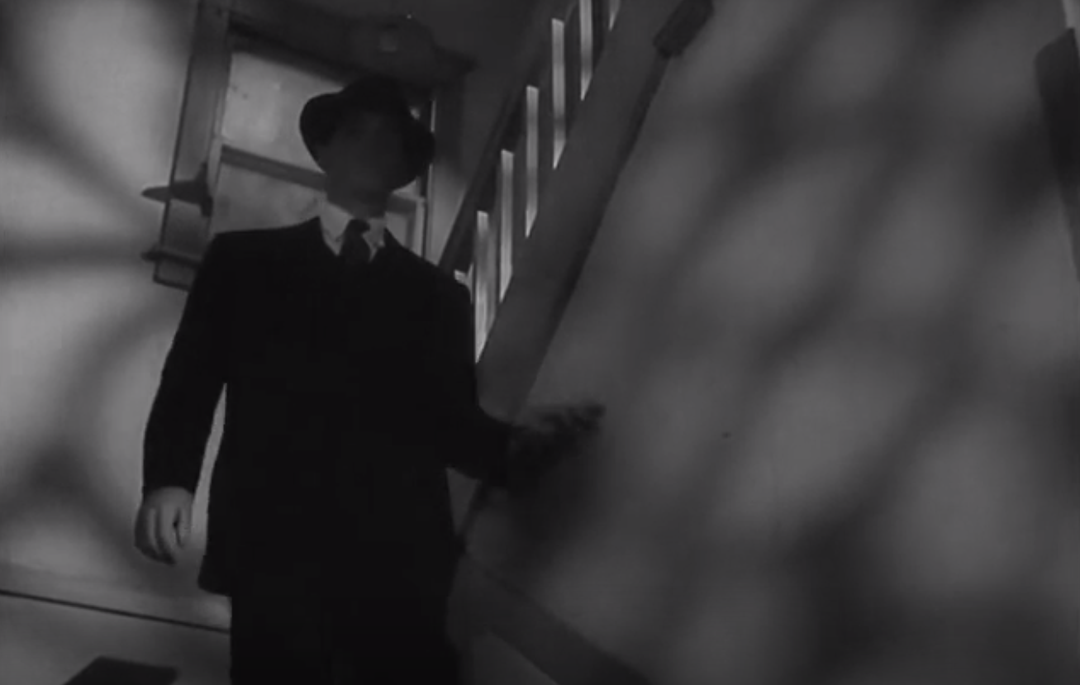

M (1931)

Provocative not only in its title but in its way of approaching a murder mystery: It is not a whodunit but a study of mass hysteria, mob mentality and the justice system. All performances in here are inarguably great, most notably the central performance by Peter Lorre. And as if Fritz Lang did not reshape cinema enough with the film's innovative visual style, he also applies the medium of sound in ways no other has done so before. And, to be frank, I can’t name another movie since that uses sound as innovatively as this 90+ year old masterpiece.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

In 1934, the motion picture production code was properly enforced, which put defined limits on what US filmmakers could show and not show. In the years before that, the so-called “pre-code” days, there was an array of films that played with the limits of what was deemed socially acceptable. Hawks’ Scarface (1932) is the most violent example of a gangster film from that period, while All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) can be seen as one of the early definitive (anti-)war films. Yet pre-code also included many movies that played with sexual themes, and if there was one director at the forefront of that cinematic movement, it was Ernst Lubitsch. Furthermore, if there is one movie in his then-filmography that perfectly encapsulates what his style and pre-code in general stands for, it is Trouble In Paradise. It starts with one of cinema’s best openings ever, and it doesn’t take a wrong step at any point of its brief 1h 20m runtime.

-only Angels Have Wings (1939)

Howard Hawks is one of the many underappreciated directors of his period. His movies are acclaimed, but people usually don’t think of Hawks as an auteur the way they think of Hitchcock, Ford or Lubitsch. He should be seen as such though. My best guess as to why that happened is because of the wide-ranging cinematic style he was capable of: He created westerns, screwball comedies, gangster flicks and musicals. While other filmmakers often stuck to one genre and therefore would create movies immediately recognisable as their work, he tried a bit of everything preventing him to create a “trademark” like others. One of the many styles he contributed to was the adventure genre, and -only Angels Have Wings is probably his masterpiece; for it is more than just an adventure movie: Like Sunrise it mixes genres, also including aspects of comedy, romance, thriller, drama, tragedy and musical. (Yes, musical!) With its large scope, impressive acting and compelling story, this is an emotional rollercoaster if there ever was one, and arguably one of the most flawless movies ever made. I have previously described it as being a “true masterpiece on every level,” and I fully stand by that lofty claim.

Double Indemnity (1944)

One of the best parts of cinema is finding an old film noir and getting entangled in its mystery and thrilled by its suspense. The intelligent dialouge, the high-contrast visuals and the narration are all key aspects of the great style, and what better movie is there to represent it than Double Indemnity? It has all of the best parts of noir and non of the worst, presenting an array of characters that will stick with you forever and inventing a whole range of tropes that are now clichéd. Now that’s an achievement. Other noirs could equally take this place such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Big Heat (1953) or The Big Sleep (1946), but this one just seems to be that little bit more than these other three.

A Day in the Country (1946)

Filmed by Jean Renoir ten years earlier, A Day in the Country was left in an unfinished state due to bad whether during production. While that is often cited as a flaw in the movie, the broken ending actually enhances thematic conclusion of a fractured memory. The short film revolves around a central paradox: Why does Henriette remember the titular day fondly if she clearly didn’t enjoy its conclusion at the time? The audience is only left to guess what the explanation could be, but given the time period the film is set in societal standards are a plausible explanation; on that day, she probably wanted to break the engagement with her future husband, but she was scared of breaking societal rules. A reading of the equally entrancing short story by Guy de Maupassant confirms this theory. Despite explaining the paradox, the short film, however fulfilling throughout its entire painterly runtime, will leave the audience unfulfilled by the end, wanting more from the characters that have been so thoroughly and humanely studied four 40 minutes. Isn’t that one of the best thing a piece of art can do? Forcing you to watch it over and over again?

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

This can hardly be considered “Capra-Corn” considering the emotional depth this masterpiece is able to reach: It’s so much more than just a Christmas film. The most fascinating aspect is its excellent central performance by James Stewart, a performance that should be studied by all actors forever, for it is perfection. I am convinced, for instance, that it massively influenced Al Pacino’s performance in The Godfather (1972). On another note, this film is also the definitive masterpiece out of the selection of growing-old movies; movies that follow a person’s life through a framing device. (Heaven Can Wait (1943), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943, The Long Gray Line (1955), etc.)

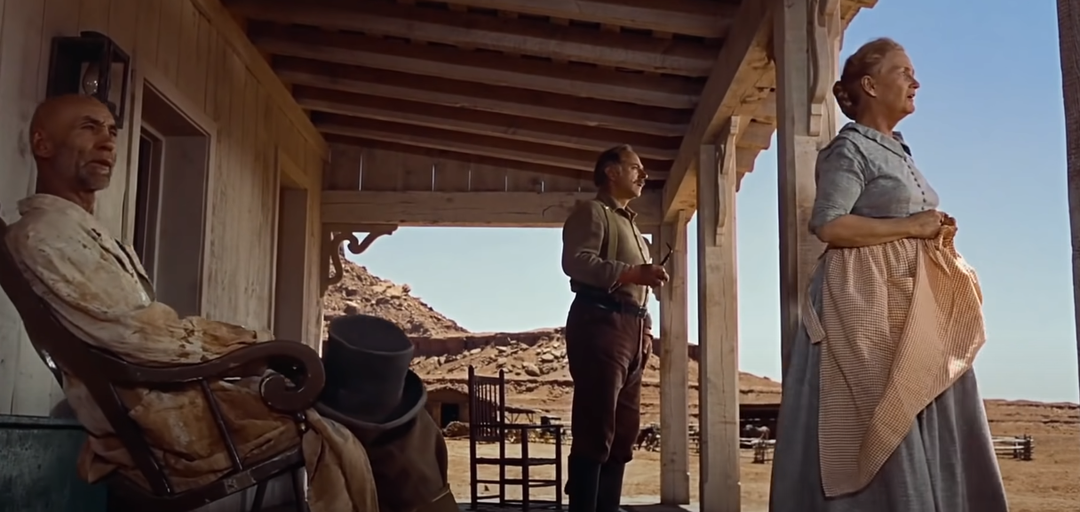

The Searchers (1956)

It has become a cliché to say that The Searchers is the “greatest western of all time” but here’s the thing: It is the greatest western of all time. Displaying some of the most beautiful images to have ever been captured in technicolour, giving us John Wayne’s most complex performance, this film was made at the height of John Ford’s creativity, and it goes to show. The number of people saying “Yeah, it’s fine, but...” makes me worry that this masterpiece is at a much greater risk of being underrated than overrated.

Vertigo (1958)

Of course, the much more boring (yet still vaguely fascinating) Jeanne Dielman (1975) has now officially surpassed Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece, but that shouldn’t distract us from how phenomenally flawless Vertigo is. As I have previously stated: “Vertigo is not merely a simple murder mystery, nor is it just a story about obsession, as it is so often described. It is a piece of art that can be analysed and interpreted in many, many ways and has been done so by people much smarter than myself. A piece of art that can be cross-examined scene-by-scene with new things to find in each scene, on each viewing.”

Raging Bull (1980)

Certainly a more modern form of cinematic bravura, but that is meant in the best way possible. Raging Bull is filled with a large amount of religious imagery and social commentary which all culminates at its final Biblical quotation that is far too often misunderstood. Raging Bull brings us what is arguably Robert De Niro's greatest performance, and it also shows director Martin Scorsese at his most visually inspiring, with stunning sound design, camerawork and editing all the way through.

Posted by Leonard Hockerts on 16/04/2023

Comments

Thanks for sharing your top ten movie list. I like how you picked different types of movies, from silent ones to westerns and more. Your list has movies from a long time ago until now, which is cool to see. Your writing about each movie helps me understand why they are important. I will certainly watch them (again)!